To begin

with, this title is absolutely correct. There are no orchids in this book for

Miss Blandish or anyone else. I don’t believe there is even a mention of

orchids, so if your name happens to be Nero Wolfe, I suggest you turn to another blog.

Otherwise,

read on.

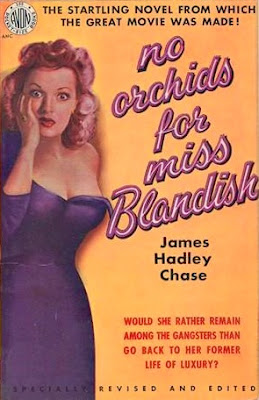

I’ve had a

book bearing this title (the Avon “Classic Crime” edition of 1961) kicking

around the house for years, but resisted reading it. Somehow I had learned it was a revised and toned-down version of the notorious original. I

mean, if I’m going to read a book famous for its brutality, why settle for a

watered-down version?

A couple of

years ago, I got curious again and tried to learn if any of the many reprint

editions contained the original 1939 text. And it just got more frustrating. Best

I could learn was that it had been officially revised by Chase (aka Rene

Brabazon Raymond) in 1942 and again in 1961, with numerous variants published

in between. I tried to track down a genuine first edition through InterLibrary

Loan, and failed that too.

So I

continued not reading it, until finally—just last year---Stark House came out

with an uncensored, unexpurgated version, featuring the original text.

Was it worth

the wait?

Well, it was

pretty dang interesting. Back in 1939, it was probably the most violent book

ever published, and I can see why it raised a ruckus. By now, I’m sure it’s

been surpassed many times, but not by anything I’ve read, or would care to

read.

The basic

plot is this: Miss Blandish (no name given), daughter of a really rich guy, is

kidnapped by a gang of brutal thugs. Almost immediately, she is re-kidnapped by

a gang of infinitely more brutal thugs. As you would expect, brutality ensues.

This continues until a private detective—relatively brutal himself, but with redeeming

senses of humor and honor—is hired to find her.

To give you

an idea of the caliber of crook she’s dealing with, her chief tormentor, Slim

Grisson, was once caught by his school master “cutting up a new-born kitten

with a rusty pair of scissors.” Slim does everything violently, right down to

way he picks his nose. Leading the gang is the kitten-cutter’s mother, who has “shoulders

like a gorilla,” and flesh hanging “in two loose sacks on either side of her

mouth.” On meeting Miss B, Ma says, “You’re going to stay here until your old

man comes across” and “If he tries to be smart, I’m going to take you apart in

bits, and those bits will be sent to your pa every goddam day until he learns

to play ball.” And she ain’t fooling.

P.I. Dave

Fenner, who makes his first appearance almost halfway into the book, knows how

to deal with such folk. Switching on a portable electric stove, he watches the

filaments turn red and says, “I could get a hell of a kick clappin’ this poultice

on that’s rat’s mug.” And he ain’t fooling, either. Later he holds a fry pan full of hissing grease over another rat and announces, “You’ll talk or I’ll

slop this fat in your mug.” The rat talks.

Chase

delivers many nice turns of phrase. As in, “There was a dead man lying on the

floor. There could be no mistake just how dead he was. The small blue hole in

the centre of his forehead told Eddie that he was as dead as a lamb cutlet.”

The story is set in the U.S., and though Chase

did pretty well with Americanese, a few British terms and spellings slipped through. Words like kerb, cheque, bell-push, boot (for trunk), grips (for suitcases) and lift (for elevator). At one point Fenner says, “It’s sweet fanny to me who

happened to Heinie. That little rat’s got nothin’ to do with me.” Sweet fanny?

The

afterword to the Stark House edition, by John Fraser, discusses the novel’s

complex publishing history and probable sources. One insight of particular

interest to me was the mention of Jonathan Latimer’s The Dead Don’t Care, published in England the year before Orchids. Fraser quotes a passage in

which Crane ponders what happens to pretty women at the hands of kidnappers.

Crane is pretty sure he knows, but wonders why no one ever talks about it.

Fraser thinks this scene may have been in Chase’s mind when he came up

with Orchids. According to Fraser,

the original 1939 text appears in a 1977 Corgi paperback and and 1961 Robert

Hale edition, both published in Great Britain. This new Stark House book (which

also contains, you may have noticed, Twelve

“Chinamen” and a Woman) appears to the first American printing of the real

thing.

P.S. In case

you missed it, over the past four days I’ve taken a nosy look at the bookshelf

of author Stephen Mertz, featuring books by Cleve F. Adams, Michael Avallone, Robert

Leslie Bellem, Carroll John Daly, Lester Dent, Donald Hamilton, Dashiell

Hammett, Robert E. Howard, Joe Lansdale, Don Pendleton, Richard S. Prather,

Bill Pronzini, Bob Randisi and others. You can view the whole shebang HERE.

I'm reading the latest STARK HOUSE omnibus edition of James Hadley Chase: JUST THE WAY IT IS and BLONDE'S REQUIEM. Art Scott has collected the cool Corgi Books editions of Chase with those wonderful wrap-around covers!

ReplyDeleteLoved the Steve Mertz Library tour! He's got some great books!

ReplyDeleteFYI:

ReplyDelete"Sweet Fanny", or more formally "Sweet Fanny Adams", is a prime example of how the British sweetened up the rougher slang terms of their times.

"Sweet Fanny Adams" derives from "Sweet F.A.", which of course refers to Great Britain's Football Association, which governs what we here in the Colonies call soccer.

As it happens, "F.A." has a different meaning, which I'm not sure I can refer to in a family blog, so there too ...

Just the Way it Is/Blonde's Requiem is in my reading stack, too, George.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Mike. Though I'm a fan of real football, and the F.A., I've never heard that expression. I know what "fanny" means (which aint' the same as this) and now, thanks to you and Google, I know what "Sweet F.A." means. It still seems mighty odd in the mouth of an American hardboiled detective.

I have read this book more than once. Chase was stark and gritty in his early novels.

ReplyDelete"Sweet Fanny Adams" refers to a child murdered and mutilated in Victorian England. At about the same time, the Royal Navy began to be supplied with tins of meat and the sailors had an obvious explanation for where the meat came from. As Mike Doran says, the term was shortened to "Sweet F. A." and was associated with a well-known phrase which also had the opening letters "F.A."...

ReplyDeleteFine review. I have an edition, but not the real deal one you read in the Stark House edition. I haven't read it, just because I haven't gotten around to it, and who knows when - if - I will.

ReplyDeletePhil read it and said he didn't think I could make it through. But it's sitting there so who knows.

ReplyDeleteI read it years ago but I don't know what edition. Not the original, I'm sure. I also saw the movie The Grissom Gang with Kim Darby as Miss Blandish. Alas, it was rewritten heavily so she could take center stage. In the book she wasn't around near as much.

ReplyDeleteBTW, I thought fanny was a British slang term for vagina.

Funny, I was just thinking about Miss Blandish yesterday, and why I just could not finish it for love or money.

ReplyDeleteEven if one gets beyond the ridiculous slang that was never spoken by anyone anywhere, the total wimpy nature of Miss Blandish herself was an insult to American women.. (although there may be British women that passive in the face of danger).

Orwell says James Hadley Chase was born when the supply of remaindered pulp magazines, which were used as ballast up 'til the war, dried up, and so the Brits had to resort to this 'ersatz' fare. "Hard cheese," as we DON'T say.